endangered

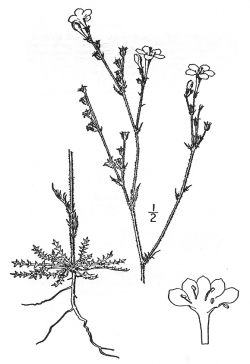

Illustration from Abrams (1951).

Photo taken at the California State University Moss Landing Marine Labs (before construction) © 1994 Dean W. Taylor.

Photo © 1994 Dean W. Taylor.

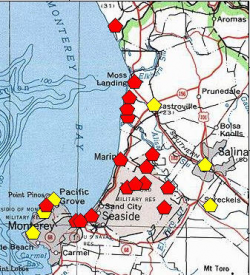

A red polygon indicates an extant occurrence; yellow indicates the occurrence has been extirpated.

This fact sheet was prepared by Dylan M. Neubauer under award NA04N0S4200074 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NOAA or the DOC.

© Copyright 2006, Elkhorn Slough Coastal Training Program

Last updated: Jun 2, 2015 15:18

Common Names - sand gilia, Monterey gilia

Family - Polemoniaceae (Phlox Family)

State Status - state threatened

(January 1987)

Federal Status - federal endangered

(June 1992)

Habitat

Open, sandy, wind-sheltered areas within beach sandwort (Artemisia pycnocephala)–coast buckwheat (Eriogonum latifolium) dune scrub or in sandy openings of maritime chaparral (most frequent where shrub cover and plant litter are low to moderate, Zoger and Pavlik 1987); 0-45 m.

Key Characteristics

Annual herb forming prostrate, basal rosette, lower branches decumbent, 6–17 cm, generally densely glandular or base tufted-woolly-hairy; rosette leaves generally serrate or once pinnate, lobes short; inflorescence open, branched; calyx densely glandular (sand grains adhering), lobes wider than membranes; corolla 10–14 mm, tube 1–2 x calyx, slender, tube = throat, 8.3–9.6 mm, throat, lobes 3–4 mm wide (4–6 mm wide in ssp. amplifaucalis), tube purple, throat part or all purple, lobes bright pink-lavender, white at base; longest stamens ± exserted, stigmas among anthers (ssp. tenuiflora has longest stamens exserted, stigmas exceeding anthers); fruit 5–6.2 mm (ssp. tenuiflora has fruit 3.5–6 mm), <= calyx. Intergrades with ssp. tenuiflora near Salinas River mouth, and approaches sympatry with ssp. amplifaucalis; width of corolla lobes and stamen length diagnostic (Porter 2013).

Flowering Period

May to June

Reference Populations

Marina State Beach, Fort Ord Dunes State Park, Fort Ord National Monument (Monterey County).

Global Distribution

Endemic to central coastal California in the Monterey Bay Region in northern Monterey and southern Santa Cruz counties.

Conservation

Extremely limited in its range, Monterey gilia is critically endangered by destruction of dune habitat and the fragmentation of remaining habitat due to development and to the negative effects of non-native, often invasive, species (USFWS 2008). As of 2008, approximately 80% of extant occurrences were lacking protection (USFWS).

Plants are adapted to germinate when conditions are favorable (USFWS 2008), responding well to competition-reducing disturbances such as fire especially where soil seed reserves are adequate (USFWS 2008). A 2005 study (Fox et al.) has shown that Monterey gilia may have long-lived seeds that persist in the soil seed bank, and Dorrell-Canepa (1994) has shown that seed production is related to plant size.

Attempt at transplantation as mitigation for Spanish Bay Golf Course failed (USFWS 2008); artificial augmentation seeding has been attempted at other sites. Plants on State Parks lands along the coast are being managed to minimize effects from recreation and invasives, especially iceplant and non-native grasses (USFWS 2008, Palkovic, pers. comm 2015). Some plants at Salinas River State Beach are intermediate in morphology to ssp. tenuiflora (Porter 2013). Genetic analysis is needed to clarify the extent of the range of this subspecies (USFWS 2008). In addition, pollination and compatibility relationships require study (cf. Grant and Grant 1965).

References

Abrams, L. R. 1951. Illustrated Flora of the Pacific States, Vol. 3. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA.

California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB). 2015. California Department of Fish and Wildlife RareFind 5. http://www.dfg.ca.gov/biogeodata/cnddb/mapsanddata.asp [15 February 2015].

CNPS, Rare Plant Program. 2015. Gilia tenuiflora subsp. arenaria, in Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (online edition, v8-02). California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA. http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/detail/868.html [accessed 15 February 2015].

Dorell-Canepa, J. 1994. Population biology of Gilia tenuiflora ssp. arenaria (Polemoniaceae). M.S. Thesis, San Jose State University. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1900&context=etd_theses [accessed 15 February 2015].

Fox, L. R. H. N. Steele, K. D. Holl, and M. H. Fusari. 2005. Contrasting demographies and persistence of rare annual plants in highly variable environments. Plant Ecology 183:157-170.

Grant, A. and V. Grant. 1954. Genetic and taxonomic studies in Gilia VIII: the cobwebby gilias. Aliso 3(3):203–287.

Grant, V. and K. A. Grant. 1965. Flower Pollination In the Phlox Family. Columbia University Press, NY.

Porter, J. M. 2013. Gilia tenuiflora subsp. arenaria, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.). Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/get_IJM.pl?tid=50823 [accessed 15 February 2015].

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Monterey gilia (Gilia tenuiflora ssp. arenaria) 5-year review: summary and evaluation. Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, Ventura, CA. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc1899.pdf [accessed 15 February 2015].

Zoger, A. and B. M. Pavlik. 1987. Marina Dunes Rare Plant Survey.